- Above the Fold: Understanding the Principles of Successful Web Site De

- Adapting to Web Standards

- Art of Non-Conformity

- Art of Readable Code

- Art of SEO

- Back to the User

- Beginning PHP6, Apache, MySQL Web Development

- Book Notes

- Books to Read

- Bored and Brilliant

- Born For This

- Choosing A Vocation

- Complete E-Commerce Book

- Content Inc

- Core PHP Programming

- CRM Fundamentals

- CSS Text

- Dealing with Difficult People

- Defensive Design for the Web

- Deliver First Class Web sites

- Design for Hackers: Reverse-Engineering Beauty

- Designing Web Interfaces

- Designing Web sites that Work: Usability for the Web

- Designing with Progressive Enhancement

- Developing Large Web Applications

- Developing with Web Standards

- Economics of Software Quality

- Effortless commerce with php and MySQL

- Epic Content Marketing

- Extending Bootstrap

- Foundation Version Control for Web Developers

- Guerrilla Marketing for a Bulletproof Career

- HACKING EXPOSED WEB APPLICATIONS, 3rd Edition

- Hacking Web Apps

- Happiness At Work

- Implementing Responsive Design

- Inmates Are Running the Asylum

- Instant LESS CSS Preprocessor How-to

- jQuery Pocket Reference

- Letting Go of the Words

- Lost and Found: A Painfully Honest Field Guide to the Startup World

- Making Every Meeting Matter

- Manage Your Day to Day

- Marketing to Millenials

- Mobile First

- Monster Loyalty

- More Eric Meye on CSS

- Official Ubuntu Book

- Organized Home

- Pay Me… Or Else!

- Perennial Seller

- Pet Food Nation

- PHP 5 E commerce Development

- PHP In a NutShell

- PHP Refactoring

- PHP5 and MySQL Bible

- PHP5 CMS Framework Development

- PHP5 Power Programming

- Preventing Web Attacks with Apache

- Pro PHP and jQuery

- Professional LAMP

- Purple Cow: Transform Your Business

- Responsive Web Design with HTML and CSS3

- Responsive Web Design with HTML5 and CSS3

- Rules of Thumb

- Saleable Software

- Search Engine Optimization Secrets

- Securing PHP Web Applications

- Serving Online Customers

- Simple and Usable Web, Mobile and Interaction Design

- Smart Organizing

- Smashing UX Design: Foundations for Designing Online User Experiences

- Studies in History and Philosophy of Science

- Talent is Not Enough

- The 10x Rule

- The Benefits of Working with Git In Your Software Projects

- The Clean Coder

- The Herbal Handbook for Home & Health

- The Life-changing Magic of Tidying up

- The Modern Web

- Think First

- This Is Marketing

- Traction

- Version Control with Git, 2nd Edition

- Web Analytics 2.0: The Art of Online Accountability and Science of Cus

- Web Site Usability: A Designer's Guide

- Web Word Wizardry

- Web Word Wizardy

- Website Owner’s Manual

- Whats Stopping Me

- Work for Money, Design for Love

- Your Google® Game Plan for Success: Increasing Your Web Presence with

- Checklists I Have Collected or Created

- Crafts To Do

- Database and Data Relations Checklist

- Ecommerce Website Checklist

- Learning Stuff From Blogs

- My Front End UI Checklist

- New Client Needs Analysis

- Newsletters I Read

- Puzzles

- Style Guides

- User Review Questions

- Web Designer's SEO Checklist

- Web site Review

- Website Code Checklist

- Website Final Approval Form

- Writing Content For Your Website

- Writing Styleguide

- Writing Tips

- 7 essentialls of graphic design

- Accidental Creative

- Choosing the right color for your logo

- CMS Design

- Communicating Design: Developing Web Site Documentation for Design and

- Designing for Web Performance

- Eat That Frog

- Elements of User Experience

- Flexible Web Design

- Forms that Work: Designing Web Forms for Usability

- Homepage Usability

- Responsive Web Design

- Seductive Interaction Design: Creating Playful, Fun, and Effective Use

- Strategic Web Designer

- Submit Now: Designing Persuasive Web sites

- The Zen of CSS Design

- Complete Book of Potatoes

- Creating Custom Soil Mixes for Healthy, Happy Plants

- Edible Forest Garden

- Garden Design

- Gardening Tips and Tricks

- Gardens and History

- Herbs

- Houseplants

- Light Candle Levels

- My Garden

- My Garden To Plant

- Organic Fertilizers

- Organic Gardening in Alberta

- Plant Nurseries

- Plant Suggestions

- Planting Tips and Ideas

- Root Cellaring

- Things I Planted in My Yard

- Way We Garden Now

- Weed Decoder

- 101 Organic Gardening Hacks

- 2015 Herbal Almanac

- Beautiful No-Mow Lawns

- Beginner's Guide to Heirloom Vegetables

- Best of Lois Hole

- Design in Nature

- Eradicate Invasive Plants

- Gardening Books to Read

- Gardens West

- Grow Organic

- Grow Your own Herbs

- Guerilla Gardening

- Heirloom Life Gardener

- Hellstrip Gardening

- Indoor Gardening: The Organic Way

- Landscaping with Fruits and Vegetables

- Real Gardens Grow Natives

- Seed Underground

- Small plot, high yield gardening

- Thrifty Gardening from the Ground Up

- Vegetables

- Veggie Garden Remix

- Weeds: In Defense of Nature's Most Unloved Plants

- What Grows Here

- Activities for Kids

- Animals In My Yard

- Baking & Cooking Tips

- Bertrand Russell

- Can I Get that on Sale?

- Cleaning Tips and Tricks

- Colour Palettes I Like

- Compound Time

- Cooking Tips

- Crafts

- Crafts for Kids

- Even More Quotes

- Household Tips

- Inspiration

- Interesting

- Interior Design

- Keywording & Tags

- Latin Phrases

- Laundry Tips

- Learn Something New

- Links, Information, and Cool Videos - Stuff for My Kids

- Music Websites for Parents and Kids

- My Miscellany

- Organizing

- Quotes

- Reading List

- Renovations

- Silly Sites

- Things that Make Me Laugh

- Videos to Watch

- Ways to Be Nice

- YouTube Hacks

- Bug Tracking Tool

- Business Tips

- Code Packages I Like on GitHub

- Content Management systems

- Creating Emails & Email Newsletters

- Games

- I Made A Framework

- Open Source

- Patterns, Textures and other media

- PHP Coding Standards

- Programming

- Project Verbs for to do lists

- Qualities of Creative Leaders

- Scalable Vector Graphics

- SEO

- Software Design

- The Shell, Scripts and Such

- Writing Instructions

- Accessibility

- CSS Frameworks

- CSS Reading List

- CSS Sticky Footer

- Design of Sites

- htaccess files

- HTML Tips and Tricks

- Javascript (and jQuery)

- Landing Page Tips

- Making Better Websites

- More Information on CSS

- MySQL and Databases

- Navigation

- Responsive Design

- Robots.txt File

- Security and Secure Websites

- SVG Images

- Types of Content

- UI and UX and Design

- Web Design and Development

- Web Design Tools

- Web Error Codes

- Website Testing Checklist

- Writing for the Web

- Writing Ideas for your website

- Animations and Interactions

- Being a Better Designer

- Bootstrap Resources

- Color in Web Design

- Colour

- CSS Preprocessors: Sass and Less

- CSS Tips Tricks

- Customer Centered Design Myths

- Design Systems

- Designing User Interfaces

- Font & Typographical Inspiration

- Fonts, Typography, Letters & Symbols

- Icon Sets

- Icons

- Logo Designs

- Photoshop Tips and Tricks

- Sketch

- UX and UI and Design Reading List

- Web Forms

- Well Designed

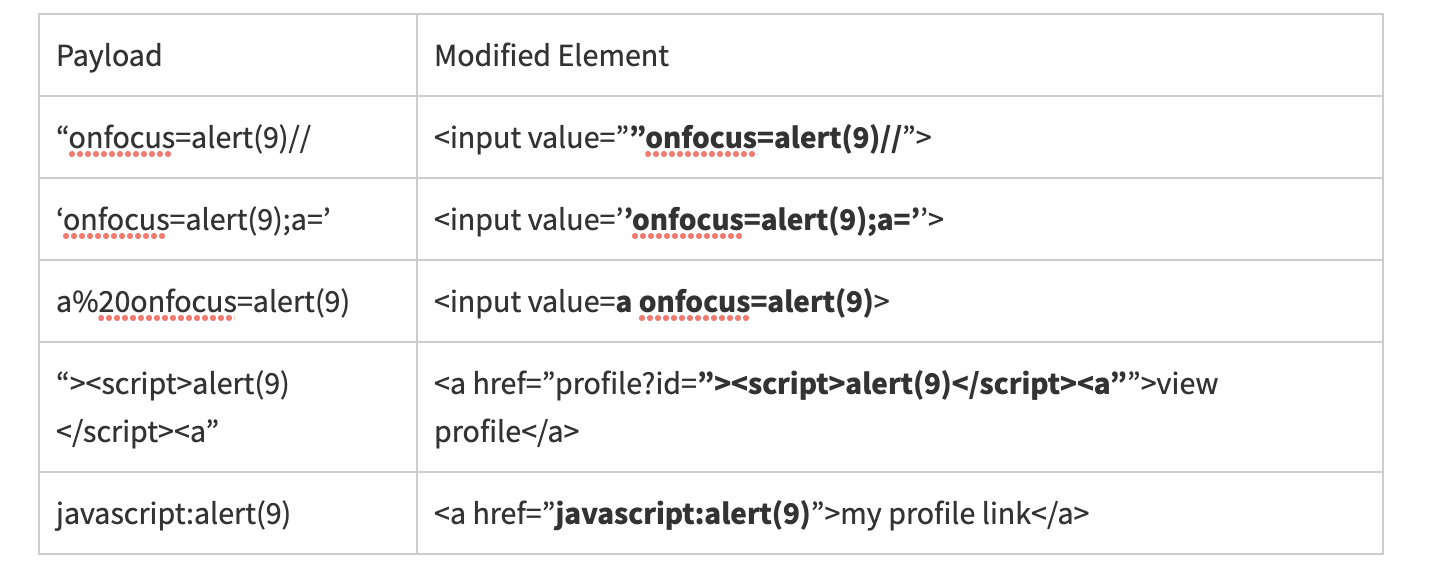

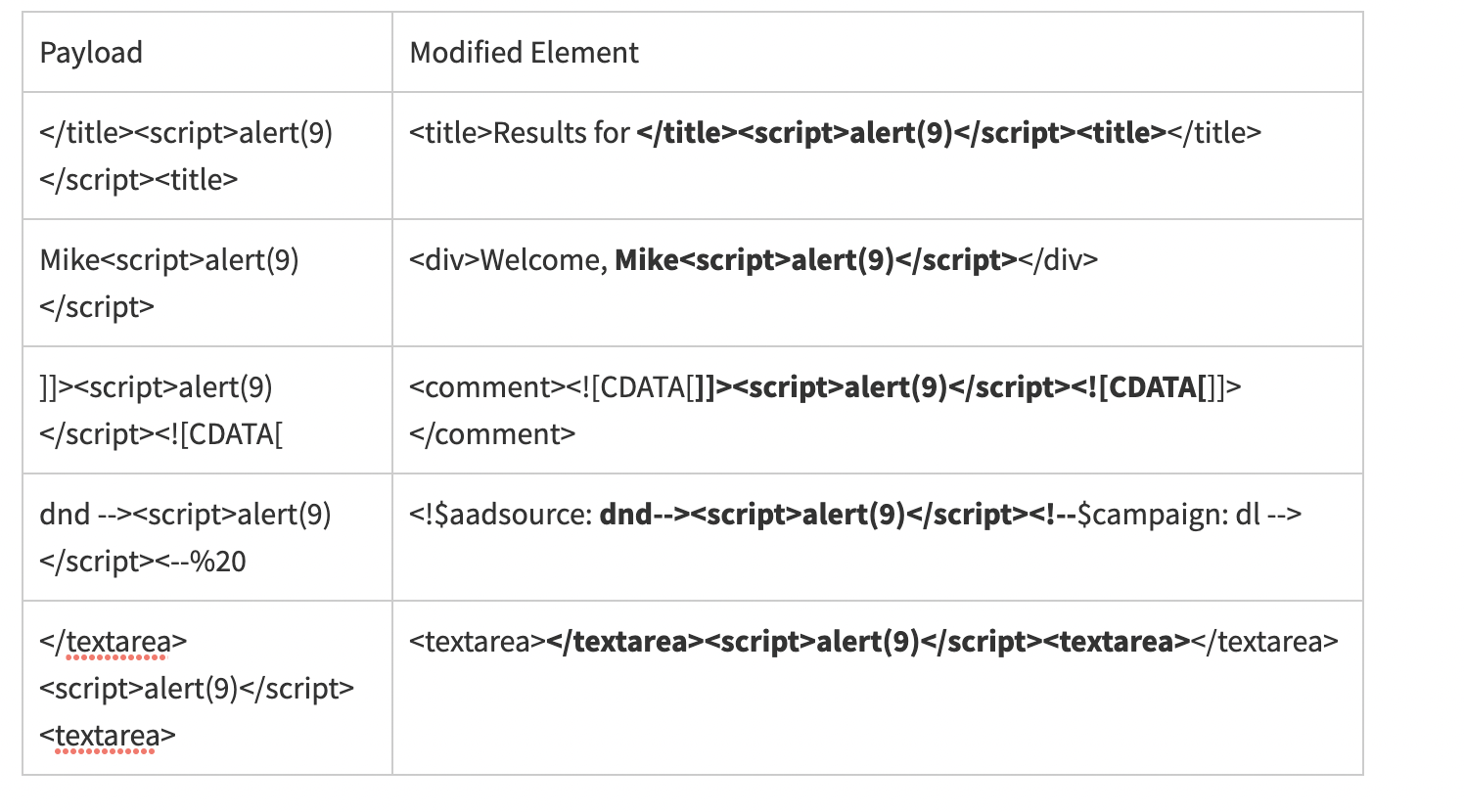

Understanding HTML Injection

HTML injection is a basic security weakness in which data (information like an email address or first name) and code (the grammar of a web page, such as the creation of script tag elements) mix in undesirable ways.

An XSS attack rewrites the structure of a web page or executes arbitrary JavaScript within the victim’s web browser. XSS comes into play when the visitor can use characters normally reserved for HTML markup as part of the search query.

Each of the previous examples demonstrated an important aspect of XSS attacks: the context in which the payload is echoed influences the characters required to hack the page. In some cases, new elements can be created such as script tag or iframe. In other cases, an element’s attribute might be modified. If the payload shows up within a JavaScript variable, then the payload need only consist of code.

More vicious payloads have been demonstrated to:

- steal cookies so attackers can impersonate victims without having to steal passwords;

- spoof login prompts to steal passwords (attackers like to cover all the angles);

- capture keystrokes for banking, e-mail, and game websites;

- use the browser to port scan a local area network;

- surreptitiously reconfigure a home router to drop its firewall;

- automatically add random people to your social network;

- lay the groundwork for a Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF) attack.

Form Fields

Forms collect information from users, which immediately make the supplied data tainted. The obvious injection points are the fields that users are expected to fill out, such as login name, e-mail address, or credit card number. Less obvious are the fields that users are not expected to modify such as input type=hidden or input fields with the disable attribute. A common mistake among naive developers is that if the user can’t modify the form field in the browser, then the form field can’t be modified.

A common example of this attack vector is when the site populates a form field with a previously supplied value from the user. We already used an example of this at the beginning of the chapter. Here’s another case where the user inserts a quotation mark and closing bracket (“>) in order to close the input tag and create a new script element.

Element Attributes

HTML element attributes are fundamental to creating and customizing web pages. Two attributes relevant to HTML injection attacks are the href and value.

The single- and double-quote characters are central to escaping the context of an attribute value. As we’ve already seen in examples throughout this chapter, a simple HTML injection technique prematurely terminates the attribute, then inserts arbitrary HTML to modify the DOM.

All elements can have custom attributes but these serve little purpose for code execution hacks. The primary goal when attacking this rendering context is to create an event handler or terminate the element and create a script tag.

Why Encoding Matters for HTML Injection

The previous discussions of percent-encoding detoured from XSS with demonstrations of attacks against the web application’s programming language (e.g. Perl, Python, and %00) or against the server itself (IIS and %c0 %af). We’ve taken these detours along the characters in a URI in order to emphasize the significance of using character encoding schemes to bypass security checks.

The angle brackets (< and >), quotes, and parentheses are the usual prerequisites for an XSS payload. If the attacker needs to use one of those characters, then the focus of the attack will switch to using control characters such as NULL and alternate encodings to bypass the web site’s security filters.

Probably the most common reason XSS filters fail is that the input string isn’t correctly normalized.

Often the impact of HTML injection hack is limited only by the hacker’s imagination or effort. Regardless of whether you believe your app doesn’t collect credit card data and therefore (supposedly!) has little to risk from an XSS attack, or if you believe that alert() windows are merely a nuisance—the fact remains that a bug exists within the web application. A bug that should be fixed and, depending on the craftiness of the attacker, will be put to good use in surprising ways.

Bibliographic Information

Hacking Web Apps

These are notes I made after reading this book. See more book notes

Just to let you know, this page was last updated Monday, Feb 02 26